Most people think that time zones are just stripes of land spreading from the North Pole to the South Pole at regular intervals, but the reality is much more complicated. Time zones usually follow political and historical borders rather than geographical ones, which often leads to shapes and conventions that look completely absurd.

To understand the examples below, note that time zones are defined relative to the UTC (Coordinated Universal Time), which, roughly speaking, corresponds to time measured in London, UK (if we ignore Daylight Saving Time). By the way, the abbreviation UTC is yet another historical oddity: English speakers wanted the abbreviation to be CUT, whereas French speakers wanted TUC (“temps universel coordonné”). UTC emerged as a compromise between the two—so it, in fact, does not stand for anything.

For example, Los Angeles is in the UTC−8:00 time zone (often abbreviated as UTC–8), which means that the time there is the time in London minus 8 hours (the “–8:00” part is called the “offset”). Similarly, Tokyo is in the UTC+9:00 (or UTC+9) time zone, so the time there is the time in London plus 9 hours (ignoring Daylight Saving Time).

Without further ado, let’s take a look at the strangest facts about time zones:

5. Some countries use half-hour and quarter-hour offsets

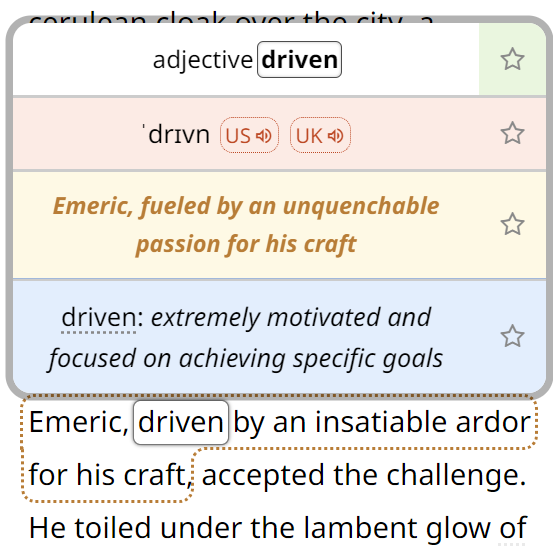

People usually think that time zones are determined by whole numbers. While this is true for most time zones, countries in Southern Asia commonly use time zones with an offset that is a multiple of 30 minutes. Most notably, the whole of India lies in the time zone UTC+5:30, as a result of which every fifth person in the world lives in a time zone with a fractional offset:

If you look carefully, you will notice that Nepal lies in an even weirder time zone: UTC+5:45. If you cross the border from India to Nepal, you will have to set the time on your watch 15 minutes forward, and if you move just 150 km (93 mi) further north and cross the Chinese border, the time suddenly jumps 2 hours and 15 minutes forward.

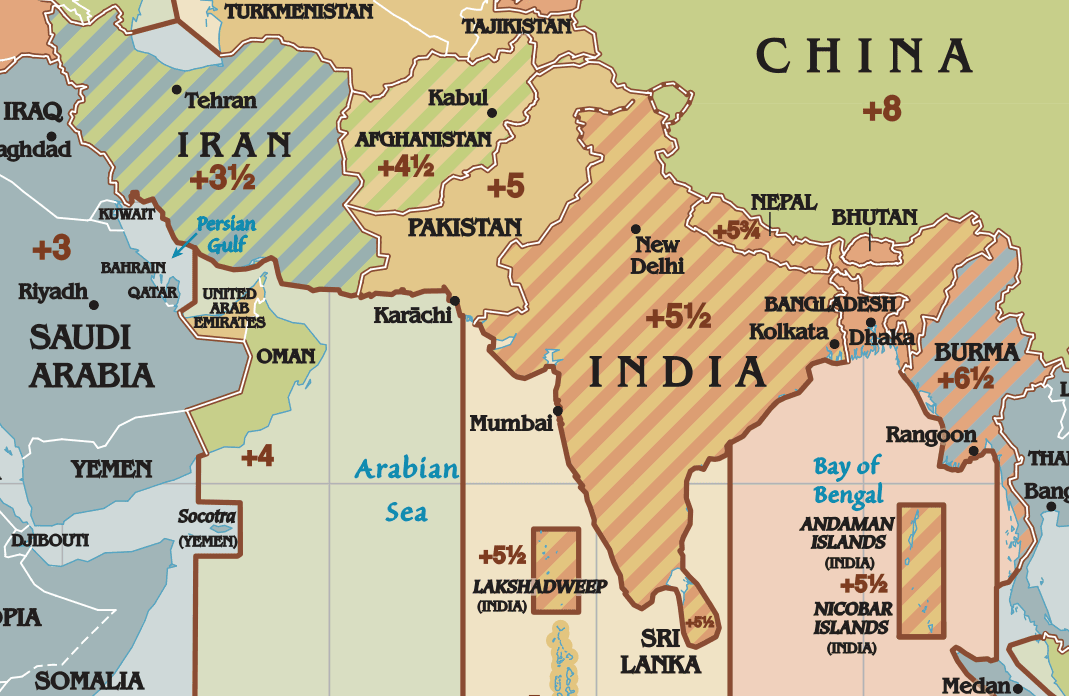

However, not just Asian countries use fractional offsets. One third of Australia does the same—the Northern Territory and South Australia use UTC+9:30, and the Howe Island has UTC+10:30:

Oddly enough, South Australia observes Daylight Saving Time, whereas the Northern Territory does not, so from October until April, these territories use different fractional offsets. There are a few other regions using a fractional offset, such as Newfoundland in Canada (UTC–3:30).

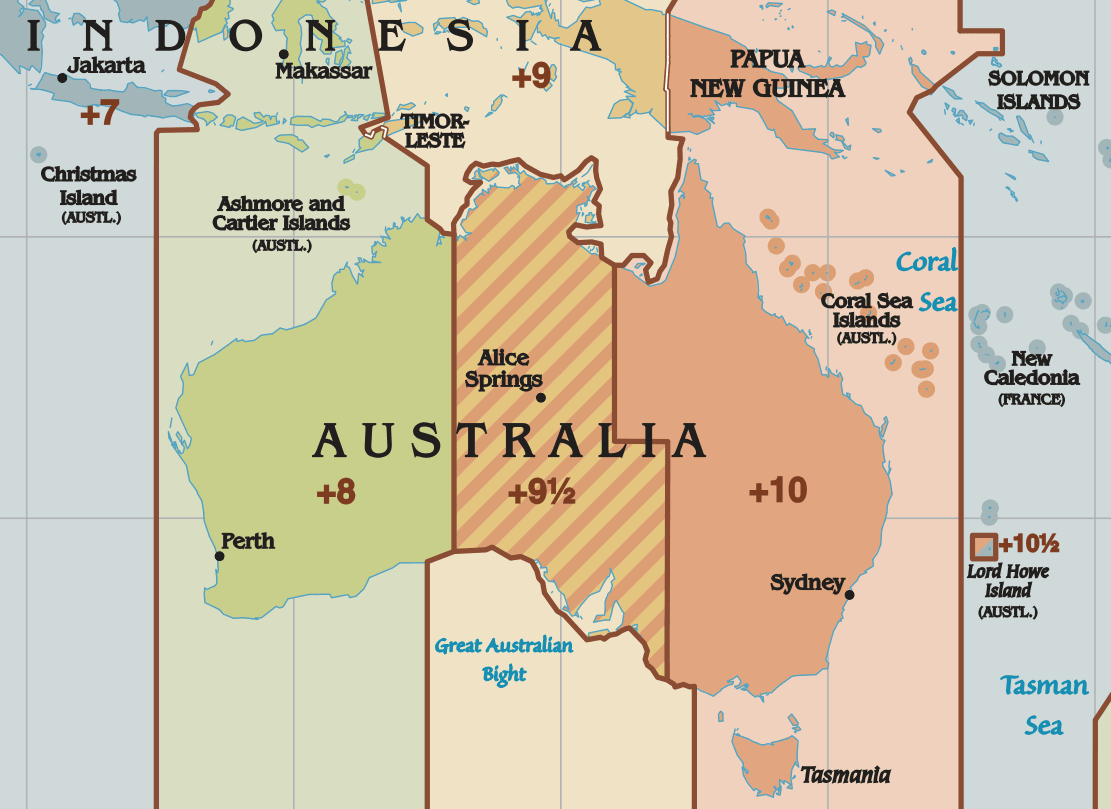

4. China has only one huge time zone

China is a huge country, spanning about 5000 km (3100 mi) from east to west, which is more than the continental United States (excluding Alaska). As you can see from the map below, the neighbouring countries of China (most notably Russia) manage to squeeze 7 different time zones (from UTC+5 to UTC+11) into the same geographical span, while China officially uses just one.

This, of course, causes a few problems. In some parts of China, people have to wait until midnight before it gets dark, and the sun does not rise until 10 AM in the winter.

Furthermore, in Xinjiang, a large autonomous region in the west of China, about half of the population uses the official Beijing standard time, while the other half uses the local UTC+6 standard. As you can imagine, this is a common source of confusion, especially among tourists.

3. Travelling between “neighbouring” time zones sometimes means adding or subtracting more than just an hour

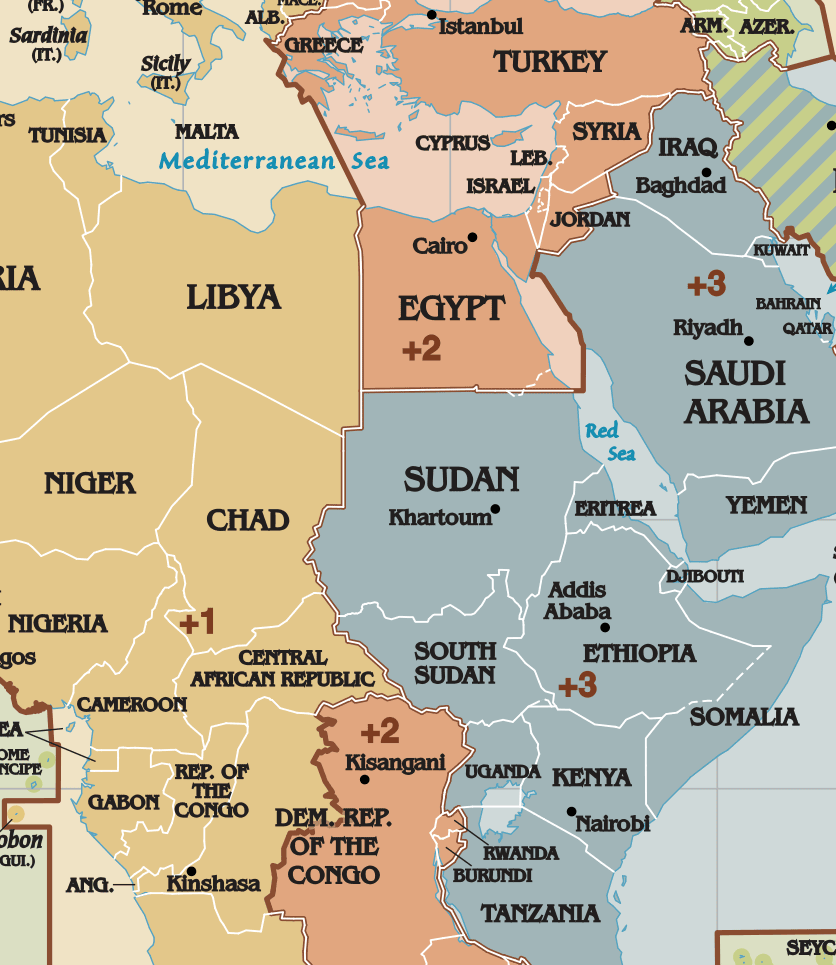

This one should be rather clear from the example above, as going from China to almost anywhere will force you to adjust the time on your watch by more than an hour, but at least it makes sense for everyone in one country to use the same time standard. However, such leaps sometimes happen for no apparent reason, as in the following example in Africa:

The UTC+2 time zone is “broken”. When you cross the border from Chad to Sudan or from the Central African Republic to South Sudan, be prepared to add 2 hours to your clock. Of course, there are political and historical reasons for this inconsistency, but it would be more logical for Sudan and South Sudan to be in the UTC+2 time zone rather than UTC+3.

2. UTC+12 and UTC–12 are the same time zone… with a different date

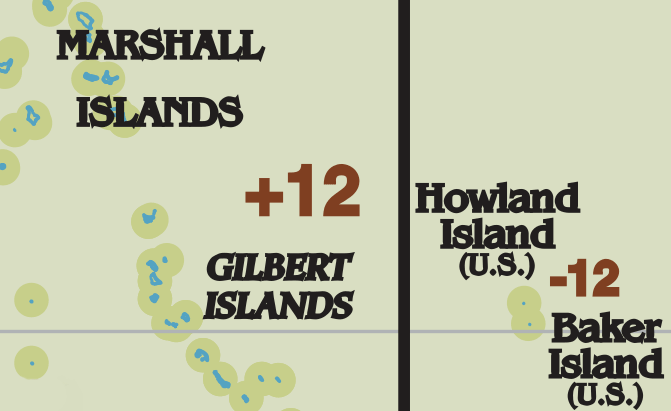

If you travel 180 degrees of longitude from London in either of the two possible directions, you will end up in the same spot on the other side of the globe. This means that the UTC+12 and UTC–12 time zones should theoretically cover the same area… but they are 24 hours apart. This is why this time zone is split into two “sub-zones” of equal width (fully applying only in international waters), one being 12 hours ahead of London and the other being 12 hours behind.

There are only two pieces of land in the world in the UTC–12 time zone: Baker Island and Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean (both being territories of the United States). They are uninhabited, and technically their time zone is left unspecified, but they belong to the UTC–12 nautical time zone.

If you left the Gilbert Islands (UTC+12, see the map above) on a boat and arrived at Baker Island or Howland Island, your watch would still be showing the correct time, but if it has a date display, the date would be one day off. However, this is, surprisingly, not the only case where this happens, because:

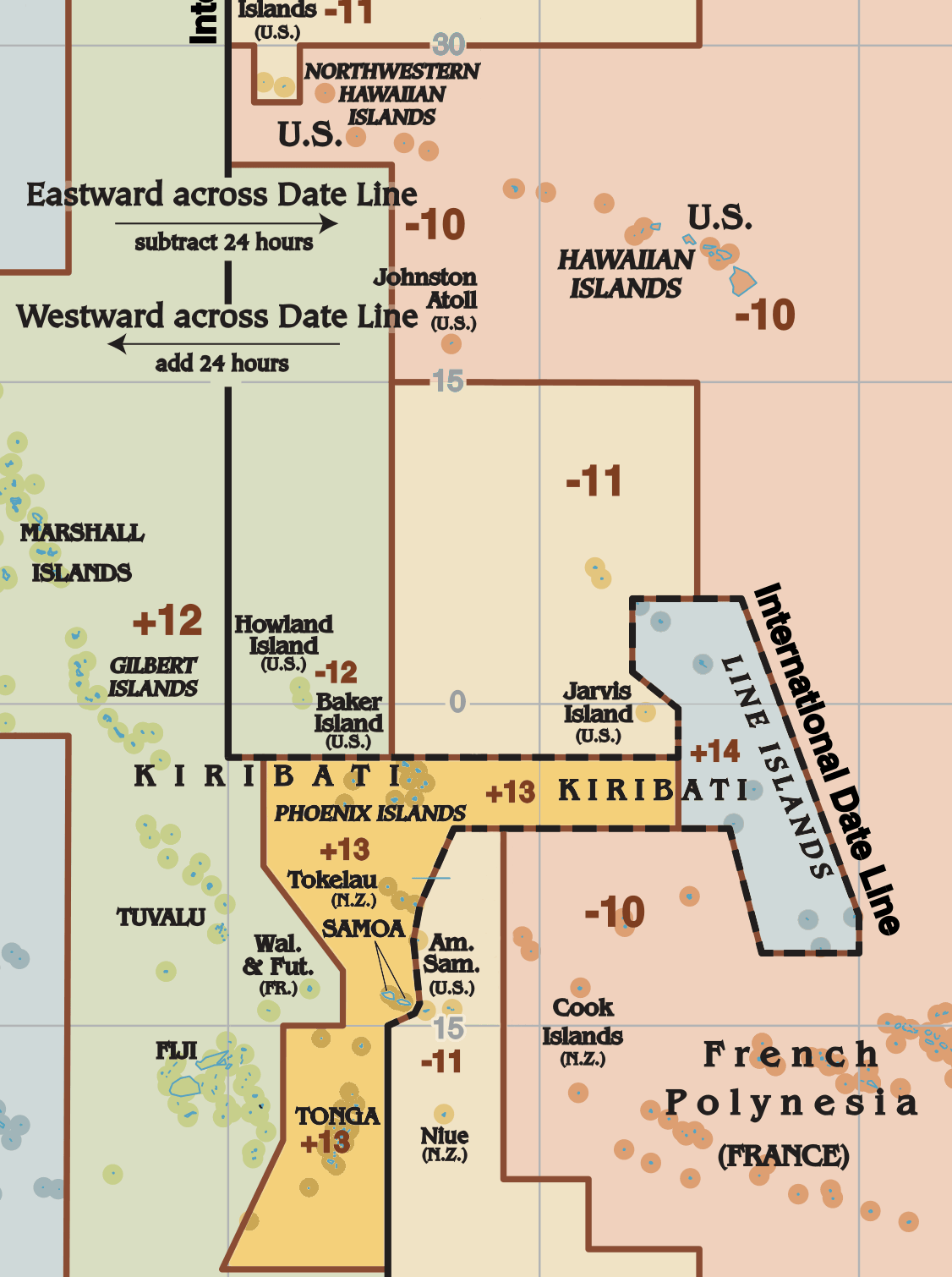

1. There are time zones beyond UTC+12

This is probably the strangest thing about time zones. A few islands in the Pacific Ocean use the UTC+13 time zone (Tonga, Samoa, Tokelau) and even the UTC+14 time zone (the Line Islands, most notably Kiritimati) instead of the usual UTC–11 and UTC–10:

This means that the time on the Line Islands is 1 day and 2 hours (26 hours) ahead of Baker Island (UTC–12, mentioned above) and 25 hours ahead of nearby Jarvis Island. To imagine what that means, take the following example:

Nevertheless, you are unlikely to be able to pull this bizarre stunt, since Jarvis Island has the status of a national wildlife refuge, and you’d need a special permit to visit it, which is typically only granted to researchers. If you don’t get a permit, you could try to fly to American Samoa (which is also in UTC–11), but good luck catching a plane that can make 2400 km (1490 mi) in under an hour…

If all you want is a way to get drunk two days in a row without looking like an alcoholic, you could celebrate New Year’s Eve on Kiritimati, fly to Hawaii the next day, and celebrate New Year’s Eve again at the same time as the day before (Hawaii is 24 hours behind Kiritimati, even though they are located at exactly the same longitude). An even cheaper option would be to take a ferry from Samoa (UTC+13) to American Samoa (UTC–11), which are only 70 km (43 mi) apart.

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a  Web App

Web App