Whenever I publish a language map, such as the one of the languages of Europe, I get comments claiming that “Xyz is not a language”. For example, some people have claimed that Swiss German “is not a language” or that Silesian is “just a dialect of Polish”. I believe that this attitude stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what a language actually is, so I decided to write an article to make that clear.

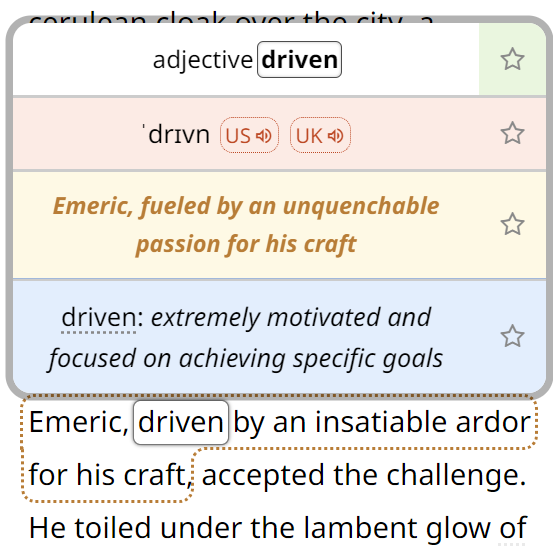

When you look up the term “language” in a dictionary, the definition usually goes along the lines of:

Assuming this definition, the ways people in Switzerland or Silesia speak obviously are languages, so why do so many people insist they are not?

Some people feel that a language is not a “real” language unless it has a codified written form. However, such a statement makes little sense, since every single language people speak today has not had a written form at some point in the past, and surely it did not start being a language only after a few monks scribbled some notes on a piece of parchment.

A more common reason why people don’t consider a certain language to be a language is that it is, as they say, “just a dialect”. It is important to realize that the terms “language” and “dialect” are not at all mutually exclusive. To understand what such a statement means, we have to take a look at another meaning of the word “language”.

Language as a group of related languages (varieties)

If you think about it, English does not fit the definition of language given above (it is spoken in different geographical areas and cultural traditions). Does that mean that English is not a language?

One of the problems with questions about languages is that the word “language” has several different meanings. Most importantly, it is often used to refer to a group of closely related languages (closely related systems of communication). English spoken in New York is not completely the same language as English spoken in London, but they are very similar and share a common origin, so we call them “dialects” of one big “English language”.

Such groupings are sometimes rather arbitrary and exist mostly for political and historical reasons. The Chinese language, as it is often called, is a group of related languages, many of which are not mutually intelligible (some linguists compare the difference between Mandarin Chinese and Cantonese Chinese to the difference between English and Swedish). The same is the case for the Arabic language, which consists of several mutually unintelligible languages.

Mandarin and Cantonese are often referred to as dialects of Chinese in popular usage, but this is not an accurate representation of reality. One could also refer to them as Chinese languages, but that may cause confusion, since Chinese itself is usually referred to as a language.

To avoid this problem, linguists often use the term “language” only in the “group” sense and refer to its constituting smaller languages as varieties. For example, Mandarin is a variety of Chinese, and Modern Egyptian is a variety of Arabic.

What is a dialect?

The word “dialect” has three different meanings.

1) Linguists usually understand it as a mutual relationship: If two languages, A and B, are mutually intelligible and are closely historically related, linguists say that “A and B are dialects”, “A is a dialect of B”, or “B is a dialect of A” (all of these statements are equivalent). In this sense, English spoken in New York and English spoken in London can be considered dialects.

Note that there is no universally accepted criterion based on mutual intelligibility for what it means for two languages to be dialects, but two languages (varieties) are usually called “dialects” if their speakers can communicate at a reasonable speed without too many misunderstandings, without previously having been exposed to the other language.

2) Another sense of the word “dialect” is used in sociolinguistics and in informal settings. Most languages have a dominant variety that is considered standard or is given greater prestige than other varieties, which are then referred to as “dialects”. For example, Andalusian Spanish is commonly referred to as a “dialect” and Standard Spanish simply as “Spanish” in Spain, and the word “dialect” may even be used pejoratively to express that the speaker considers it in some way inferior. This approach to the definition of a dialect is nicely summarized by the following well-known adage:

3) Finally, when speaking about a language in the “group” sense, “dialect” is sometimes used synonymously with “variety”, such as in the case of Mandarin and Cantonese. Linguists generally avoid this usage when speaking about varieties that are not mutually intelligible or differ from one another to such an extent that the status of a true dialect is questionable, but there are still cases where this is the most common way to refer to mutually unintelligible varieties.

For example, Germanic languages spoken in the south of Germany and Switzerland are usually called “German dialects”, even by linguists, even though they are not mutually intelligible with Standard German.

Are dialects languages?

Now that you understand the two commonly used meanings of the word “language” and the three meanings of the word “dialect”, I hope you will agree that it does not make sense to say that a dialect is “not a language”. A dialect in any of the senses above is a body of words used for communication (a language), and a dialect in senses “2)” and “3)” can also refer to a language in the group sense.

The real question is whether a given language should be considered separate (independent) from another. This is sometimes obvious even without clarifying what is actually meant by “language”; for example, it is clear that English and Spanish are two separate languages.

In other cases, the question requires further clarification. Are Czech and Slovak separate languages? Czech spoken in Prague and Slovak spoken in Eastern Slovakia are not dialects of one another (speakers only speaking the Prague variety of Czech who are not familiar with standard Czech or Slovak would not be able to easily communicate with speakers of Eastern Slovak), while Standard Czech and Standard Slovak are close to being dialects (probably not quite there yet, but their written forms could be considered dialects), and varieties of Czech and Slovak spoken near the border between the two countries can definitely be considered dialects.

For minority languages, the question often boils down to being a dialect of a standard language (in the sense of mutual intelligibility). When someone asks, “Is Silesian a dialect?”, the question really means whether Silesian and Standard Polish are dialects.

The answer in this case is that they probably can be considered dialects of one another in terms of mutual intelligibility. However, as a result, many people inappropriately conclude that they are not different languages. Of course Silesian and Standard Polish are different; they differ in phonology, grammar, and even orthography. They are just not different enough to be mutually unintelligible. They are different but not separate.

The question could also mean whether Polish, in the “group” sense, includes Silesian as one of its varieties. Since languages in the group sense are defined subjectively rather than by objective criteria, this is not a scientific question; it is just a matter of convention, and different people, including linguists, will give you different answers.

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a  Web App

Web App