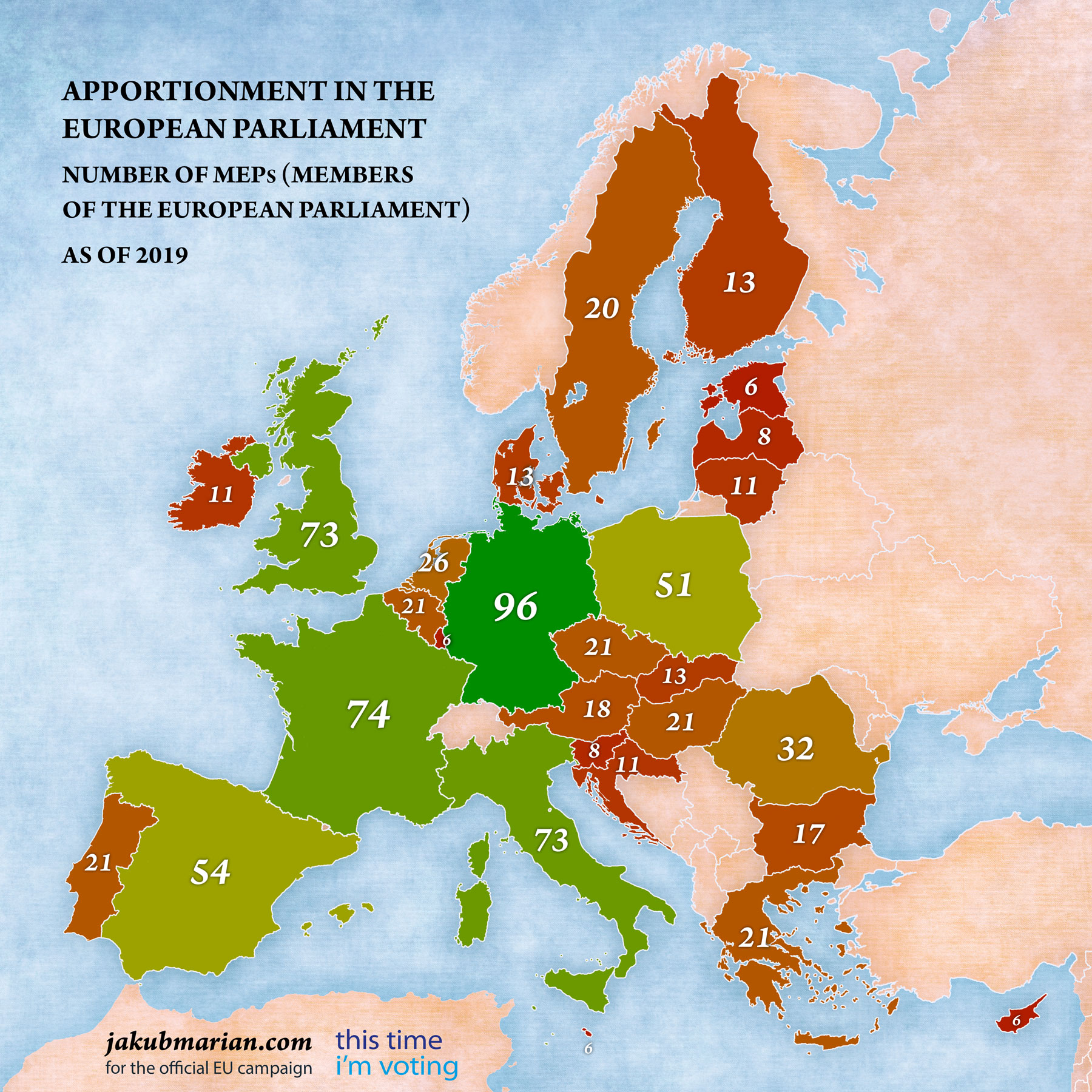

The European Elections are a fairly complex matter, which was further complicated by Brexit and its delay. There was a new agreed-upon apportionment of the European Parliament in which some of the UK’s seats were allocated to other EU members; however, this apportionment was abandoned, and each country gets the same number of MEPs (Members of the European Parliament) as in the 2014 election, which is as follows:

The fact that small countries get only a small number of seats may seem demoralizing to voters in smaller countries, but the number of MEPs itself does not tell the whole story.

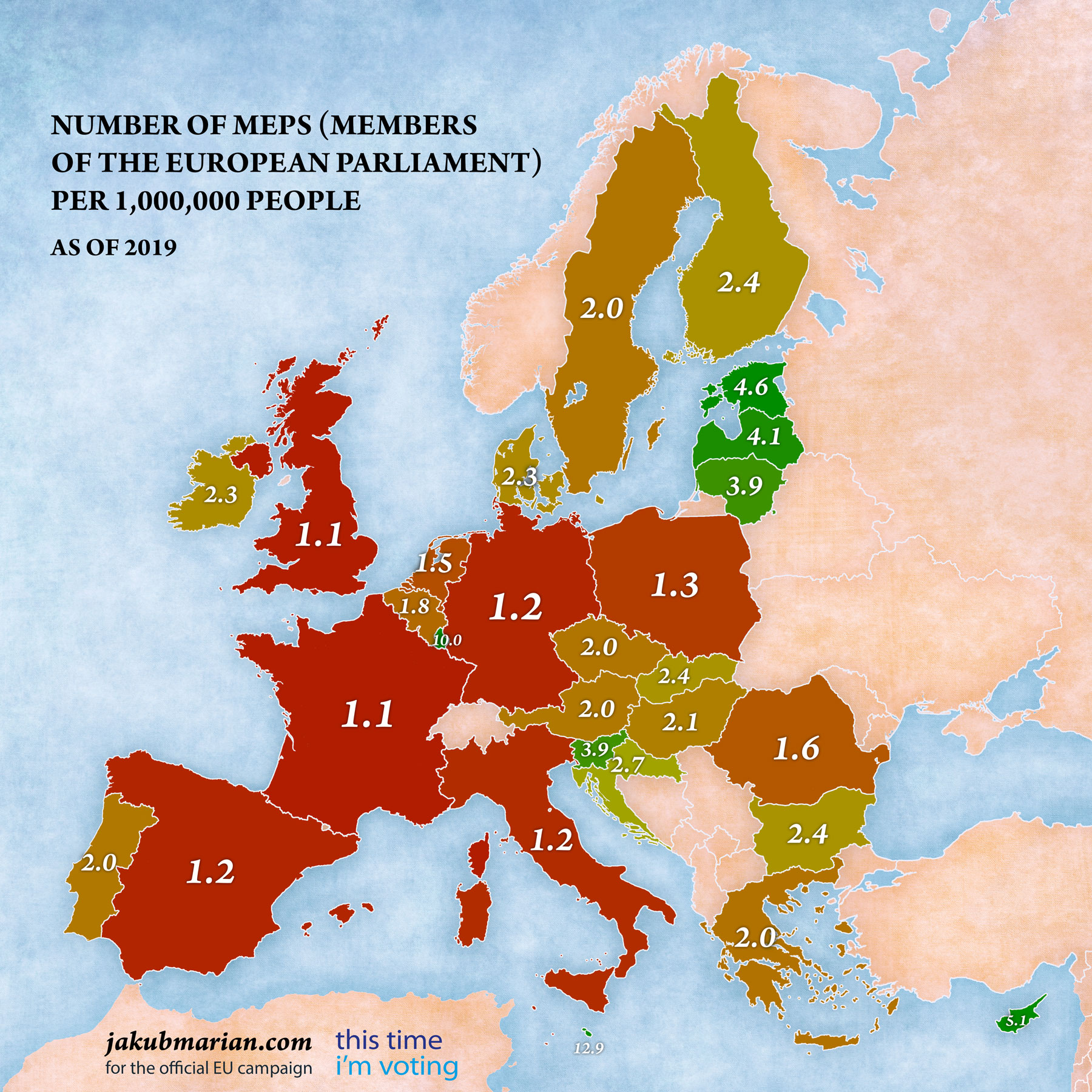

EU treaties say that the number of MEPs should be “degressively proportional” to the population of the member states, which means that the smaller a country is, the more MEPs it gets relative to what it would get if the system were completely proportional.

This is better illustrated with the following map, which shows what we could call the “voting power” of individual voters:

The figures are to be interpreted as follows. Take, for example, Sweden (2.0) and France (1.1). Suppose that everybody is going to vote (forgetting about age restrictions for now). A Swedish MEP needs 2/1.1 = 1.8 times fewer votes (on average) to be elected than a French MEP.

In other words, an individual vote in Sweden has almost twice as much “weight” compared to an individual vote in France, so voters in smaller countries actually have more influence on European politics than voters in larger countries.

It is also worth noting that the degressive principle is broken in the case of Germany, which has more MEPs per capita than the UK and France, which have a smaller population.

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a  Web App

Web App