When I wanted to start to play jazz on the guitar (after many years of playing only classical music), I was disgusted by how many things I would have to memorize although I was sure already knew them (because I could sing them, for example). I understood that within the limited time I have for playing the guitar I would never be able to play jazz at a professional level. So I decided to find a way to make things simpler.

After some experimentation, I found a tuning which I believe is the best possible guitar tuning to play jazz (or any other kind of music which wasn’t written particularly for the standard guitar tuning). It’s the major third tuning—tuning, in which the interval between adjacent strings is the major third. After I have found this tuning, I tried to look up other people on the Internet who use it, and, not surprisingly, there were some (so I am not the original inventor of this concept).

The most complete website about the tuning I have found is M3 Guitar. What I did, however, was that I tried to find the best possible physical guitar design to accommodate this tuning, and this effort resulted in the so called M-Stick.

Principles of the tuning

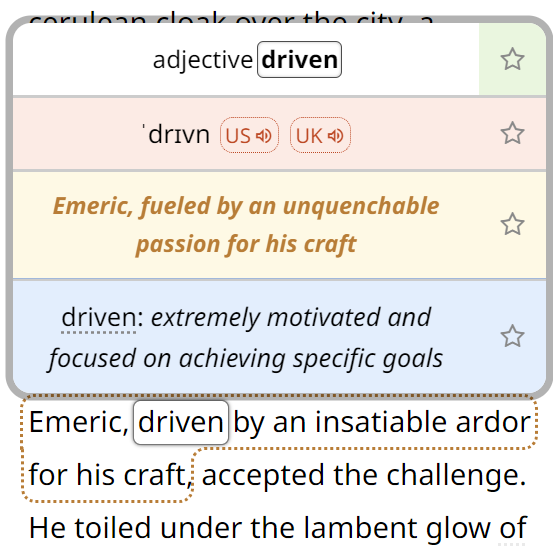

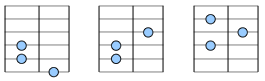

So why is this tuning so interesting? The major third interval contains four semitones and (most) people have four fingers other than the thumb; that is, the fretboard diagram for the chromatic scale (i.e. “semitone after semitone”) in the major third tuning looks as follows:

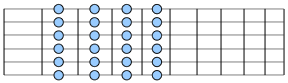

Since every scale is contained in the chromatic scale, every scale (or generally every melody) can be played in one hand position. However, the more important fact is that the tuning is “periodic”. Moving three strings up is the same as moving one octave up. This is one of the possible fingerings of the major scale:

Do you see the periodicity? After one octave (that is, three strings) you repeat the very same pattern. To move a melody one octave up, simply use the same fingering three strings higher and vice versa. But that’s not all. Let’s look at the tones of a major triad:

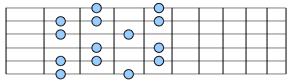

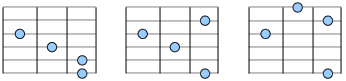

When you know how to play any single inversion of a chord, you will know how to play all inversions—simply move the bottom finger three strings up (which is one octave up) or the top finger three strings down (which is one octave down):

Directly upwards means adding the major third and up and left is the minor third—those are the building blocks of virtually all chords. Now, it shouldn’t be hard for you to draw the fretboard diagrams of a minor triad (that is, the major third above a minor third, the opposite order than in a major triad):

However, the most important thing is that the patterns apply to the whole fretboard. Wherever you use any of the shapes above (on any combination of three adjacent strings), the resulting chord type will be the same.

Conclusion

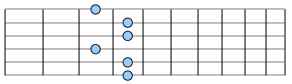

Playing inversions of chords in the standard tuning is a very hard task. This task becomes trivial in the major third tuning, where you typically don’t have to remember voicings of chords—you just see them. Consider the following example of a dominant seventh chord (like C7).

The first image shows the basic voicing – the major third, then the minor third, and then the minor third again. This voicing is virtually unplayable in the standard tuning. By taking inversions of the top three tones, we get the most usual voicings of the dominant seventh chords. In the classical tuning you would have to remember six different chord shapes (in which you wouldn’t see any logic), depending on the set of strings you play the chord on; in the major third tuning, you only need to remember one chord shape.

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a

Tip: Are you a non-native English speaker? I have just finished creating a  Web App

Web App